“I’ll wager with you. I’ll make a bet. The more you deny, the stronger I get. You start to change when I get in, The Babadook growing right under your skin. Oh, come! Come see what’s underneath!” – Mister Babadook.

Warning: the following analysis includes spoilers!

Early in writer/director Jennifer Kent’s Australian creeper The Babadook, widowed mother Amelia crawls onto the floor with her six-year-old son Samuel to check underneath his bed, ensuring there are no monsters before he turns in for the night.

The scene, repeated throughout the movie, has its roots in the seemingly everyday life of a parent calming their child’s fears but also acts as one of the film’s many metaphors to dramatize the concept of “what lies beneath.” Grounded in German expressionism, the film, like many great horror movies do, works on a psychological level as an allegory to convey the concept of suppression and repression, showing us the ill effects – including cognitive dissonance – of what happens when emotions, particularly grief, have not been dealt with.

Before delving further into the film, let’s examine expressionism and allegory to understand how they fit into the bigger picture. Expressionism is, at its bare essence, taking the internal and making it external. Expressionists seek to express meaning and emotional experiences—often radically to reflect mood and tone—rather than physical reality.

An allegory is used to convey complex ideas in ways that are more readily understood by an audience. Its difference from a mere symbol is that an allegory, at least in a story, is a narrative whose whole, much like a theme, has a meaning the author wishes to convey. The use of these two together may explain why some viewers confessed to not understanding the movie (or its ending) – though to some extent, it’s a movie that’s aimed squarely at the real fears of an older audience – at least those old enough to have children of their own and suffered loss (for that’s what many of those who do will find relatable.)

Two things that distinguish The Babadook as both expressionism and allegory are its setting and titular character, Mister Babadook, himself harboring physical traits similar to those of Dr. Caligari of Robert Weine’s 1919 expressionist classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. As noted in a previous article, Setting as an extension of your main character’s mind, and the inner turmoil and feelings of your main character can be “expressed” via a reflection in the story’s setting.

In this particular case, the film’s primary setting – the home – has a minimalist feel to it with dreary tones of dark grey and cool, steely blues that effectively convey the empty sullenness Amelia still struggles with nearly seven years after the death of her husband en route to having their first child, Samuel.

As a single mother, Amelia is forced to raise her son on her own – a task that proves to be a challenge as Samuel seems to be going through a phase where he’s, to put lightly, more than a handful, suffering from anxiety and fears that she doesn’t quite understand. These, in turn, spark her anxieties as she can no longer control them, setting off a vicious swirling of cause and effect until, much like the question of the chicken or the egg, we’re no longer sure which came first: his or hers.

As for Amelia’s personal life, we’re shown several instances of the effects of loneliness, the result of loss and not moving on, when she glances at other couples together. Whether in a parking garage or on television, they serve as a reminder of what she’s lost, as does the other, empty side of the bed she sleeps in (it’s even suggested at one point that Samuel is the reason why Amelia is unable to have a relationship when a suitor from work stops over).

Despite her insistence to her sister that she’s “Moved on,” it’s her following statement, “I don’t even mention him,” that speaks to her growing problem of suppressing his memories and grief (suppressing being the conscious act of pushing memories/thoughts away).

As a counterpoint to suppression, repression is the unconscious act of pushing memories, thoughts, or impulses that may conflict with our sense of self away. This is where the true horror of the story takes place: The Babadook is a harbinger of repressed impulses and the dissonance from within.

Although Amelia’s sister confides she “Can’t stand being around” Samuel, she points out that Amelia herself can’t stand to be around him either – but won’t admit it. Much like Beth in Ordinary People (“Mothers don’t hate their sons!”), Amelia reacts with disbelief, having repressed the negative feelings associated with her husband’s death as an indirect result of her pregnancy. After all, if she weren’t to have had Samuel, none of this would have happened.

Thus, Samuel becomes the lightning rod for all that is wrong in Amelia’s life, something she impulsively tells him, “You don’t know how many times I wished it been you instead of him that died…”

What Amelia doesn’t realize is just how much her own inability to cope with grief is contributing to Samuel’s anxiety and behavioral issues: he’s aware of its effects on her and fears for her safety to the extent he’s literally built his own self-defense mechanisms – a small catapult and gun that shoots darts – declaring he will use to “Kill the monster when it comes,” if he only knew what it was.

That monster, Mister Babadook, is a personification of her illness manifesting itself externally, first in the form of a book that foreshadows impending dread, then the threat of illness as it manifests the suppression of Amelia’s pent-up grief over her deceased husband, whose “memories” she keeps locked away in the basement and forbids Samuel to have any contact with.

While the sister and Samuel are aware of repression/suppression’s ill effects, Amelia completely denies anything is wrong. When she replies “Fine” after being asked how she’s doing by a co-worker, he reminds her that it’s ok not to be considering what she’s been through. Samuel, too young to understand the concept of suppression/repression and how they work, does understand their adverse effects and the toll it’s taking on his mother as he pleads, “Don’t let it in! Don’t let it in!” – and thus its manifestation becomes known to him as The Babadook in an attempt to understand the negative impulses from the perspective of a child’s mind.

As for the relationship between Mister Babadook and Amelia’s late husband, several story attributes draw parallels between the two: first, the arrangement of the father’s clothes on the wall in the basement echoes Mister Babadook’s appearance. When Amelia later goes to the police station, she sees a similar arrangement of clothes – but they’re Mister Babadook’s. Then, when he makes his first visit, he enters from the basement. Finally, he reveals himself to Amelia in the form of her husband, telling her, “You can bring me the boy,” which harkens back to the book’s warning: “I’ll soon take off my funny disguise, and once you see what’s underneath, you’re going to wish you were dead.”

This leads us back to the purpose of expressionism: to make the internal external, for in the end, when the disguise comes off, and we see what’s underneath, we’re left with the realization The Babadook – being an external manifestation – is really the repressed part of Amelia’s identity. In short, it is Amelia – the very worst parts, something recently discussed with the commonalities of several seminal horror films since the 1960s (both identity and the disintegration of the family playing prominent factors.)

Once again, we’ve looked into the mirror and discovered that the monster is us. As Mister Babadook creeps into Amelia’s consciousness during moments of insomnia, staring at late-night television showing old silent films, the Babadook suddenly appears in several sequences to eerie effect. In essence, this is the point at which “he gets in” and gets under her skin, the repressed negative desires and emotions coming to the surface as if she were possessed by the entity itself.

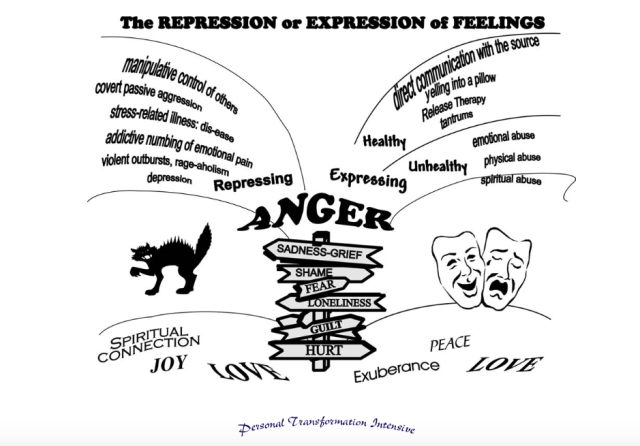

One of the ways repression of emotions manifests itself is through disease or other physical maladies, The Wellness-Institute noting

The whole concept of disease or illness is often related to emotions which have been repressed. When a person holds in anger, that angry energy has to go somewhere. Some people hold it in their jaw, others in their chest and some in their stomach. Angry energy can actually be held anywhere and everywhere in the body. This energy, if not released, then does violence to the body itself, in the form of disease. So the person that holds in their feelings and does not say what needs to be said, may experience tension in the jaw which can result in TMJ or grinding of the teeth.

This is a trait Amelia demonstrates throughout the movie, first subtly and then growing progressively worse. She continually rubs her jaw until finally pulling out a tooth. Her repressed emotions boil to the surface in a flurry of anger and resentment during the movie’s last half hour—a showdown between a mother’s conflicting emotions and the young son trying to save her from herself (not to mention his own skin.)

As an allegory for grief, it should be noted there are five stages according to the Kübler-Ross model – each represented in The Babadook:

1) Denial. This is expressed by Amelia’s telling her sister she’s coping and her refusal to believe in the manifestation of her illness as “The Babadook.”

2) Anger. We see flashes of anger from Amelia toward her sister, neighbor, and, in particular, Samuel. To some extent, she’s immediately conscious of it and tries to suppress it rather than deal with it constructively.

3) Bargaining. We see this when The Babadook reveals himself in her deceased husband’s form, telling her, “We can be together. Himself in her deceased husband’s form, telling her, “You just need to bring me the boy.” There’s also bargaining between mother and son after some of her early outbursts to regain trust.

4) Depression. It’s clear Amelia’s suffering from depression – it’s part of the environment, and her sister’s daughter openly tells Samuel they don’t ever go over to their house anymore “because mommy says it’s too depressing.”

5) Acceptance. This speaks to the movie’s conclusion, one that perhaps left a few audience members confused because they read it literally rather than as a metaphor within the context of the allegory itself: Amelia enters the basement where “The Babadook” has been repressed (or as we see, subdued), listening to its angry growls as she offers up food to it. Though clearly still afraid of it, she says repeatedly, “It’s alright. It’s alright.

Upon returning to her son in the backyard, he asks, “How was it?”

“It was pretty quiet today,” she says with a smile.

“It’s getting much better, mom.”

The scene uses this last metaphor of coping via acknowledging and facing one’s demons to impart meaning to the allegory – that we must recognize and deal with our repressed emotions to live healthier lives. It’s this act of entering the cellar (the previous subconscious realm) and identifying, facing, even “feeding” her inner fears and impulses – keeping them alive, so to speak – ultimately allowing for direct communication with the source of her problems that will enable Amelia to find some inner peace and rebuild her relationship with her son into a healthier one. In short, the trip to that dark cellar is therapeutic and an ongoing effort – something Amelia readily acknowledges now vs. being in denial before.

Written By: James P. Barker

16 Responses

Thank you.

Thank you for this wonderful and awesome review!

Thanks for spelling this out. Its the most insightful review for an easily misinterpreted movie that I have found. And one that gives it MUCH deeper meaning than what is obvious on the surface. It explains the ending perfectly. I knew the movie was flirting with the concept of “is it all in her head or is it real? ” but I hadn’t considered the idea that the babadook was a metaphor for the mother and child’s repressed grief and and other negative impulses and emotions; A simple but brilliant motif for a psychological thriller. Its not a horror film in my opinion. It really wasn’t scary in any way that I associate with that genre… But it was disturbing and original.

Thanks for the comment! It is, by classical definition of the genre, a horror film, it’s just that modern audiences have been weaned more toward the visceral rather than the thematic (I’m reminded of re-watching The Bride of Frankenstein not long ago and having similar feelings, that it wasn’t scary the least bit – yet it’s still considered at the pinnacle of Hollywood horror).

Are you familiar with Jungian psychology and Carl Jung’s conception of the “shadow self?” I see a LOT of that in the Babadook.

Yes, very familiar (Robert Mulligan’s subtle horror in “The Other” always comes to mind with regards to the concept); and I would agree, there’s a lot of it in here. Projection, the “unconscious” self being similar to the repressed, etc. It’s amazing how many different angles one can view “The Babadook” through.

excellent post, very informative. I’m wondering why the other experts of this sector do not realize this. You must proceed your writing. I am sure, you’ve a great readers’ base already!