“MYTH: ‘Show, don’t tell’ is literal-Don’t tell me John is sad, show him crying.”

REALITY: ‘Show, don’t tell’ is figurative-Don’t tell me John is sad, show me why he’s sad.”

-Lisa Cron, Wired For Story.

Lisa Cron’s Wired For Story Explains What Others Often Get Wrong About Show, Don’t Tell

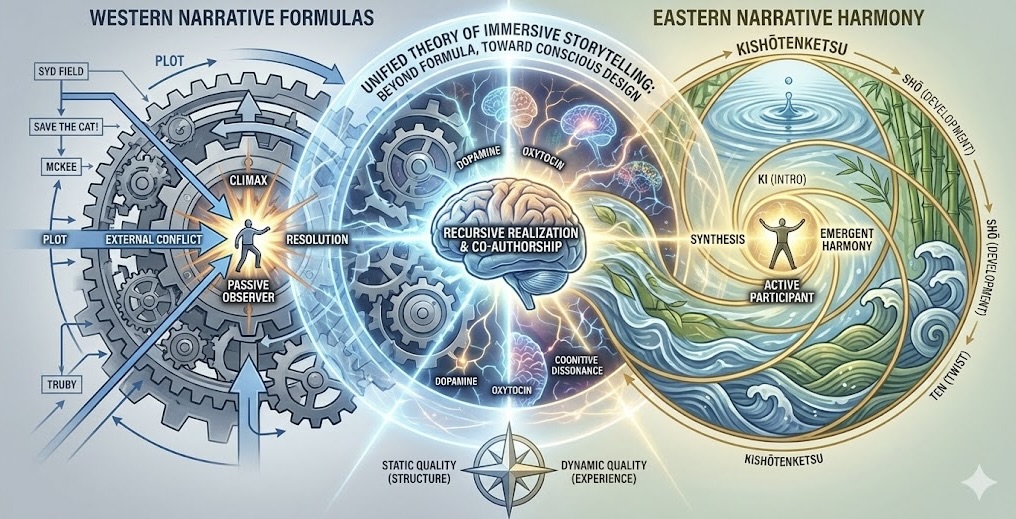

One of the most challenging things for writers is writing lean, narrative descriptions that are succinct in conveying their intended meaning to an audience. We hear the words “trust your readers” without really putting what it means into context, passages often becoming overwritten, vague, non-specific, and meaningless. Much of this comes from an inability to convey specific visual cues to the reader, making them more of a passive observer of a story rather than an active participant in it – but some issues can also be attributed to the overlooked facet of setup and pay off (the cause and effect relationship) of “Show, don’t tell.”

Understanding the virtues of both is necessary if one wants an audience to truly engage with one’s writing.

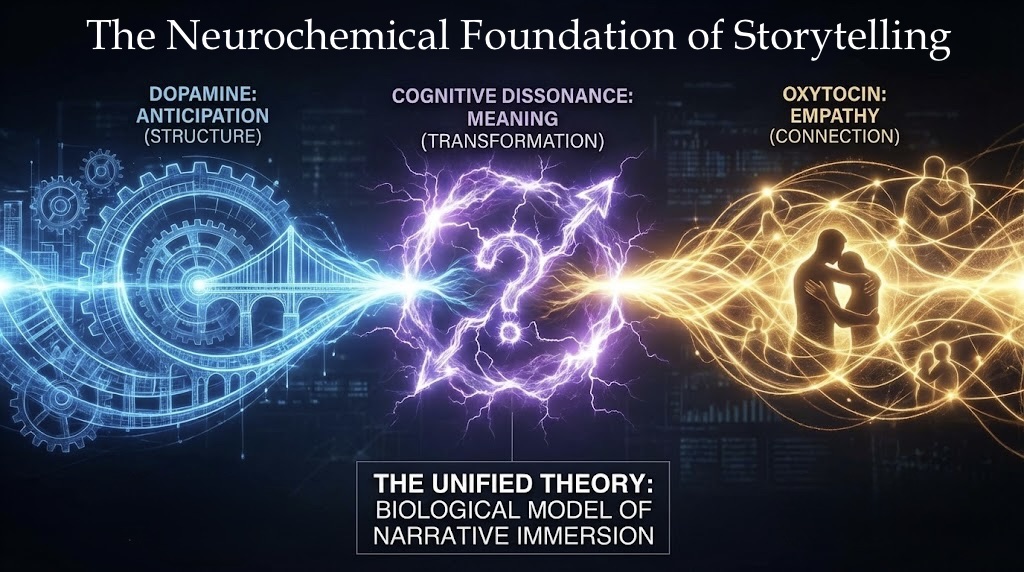

In Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers From the Very First Sentence, Lisa Cron makes the distinction between the literal and the figurative and how, all too often, writers choose to do what they believe is correct in showing an emotion as it pertains to the scene. However, they fail to recognize that in storytelling, everything is about setups (cause) and pay-offs (effect), including emotions. Showing someone crying over the death of another isn’t enough; we must have an understanding of what the deceased meant to the other for us to feel and derive meaning ourselves while watching the scene.

In other words, the setup provides context for the payoff – and you know the movies that don’t do this effectively because your friend sitting in the next seat will nudge and ask you, “Why did he do that?

So why is this important?

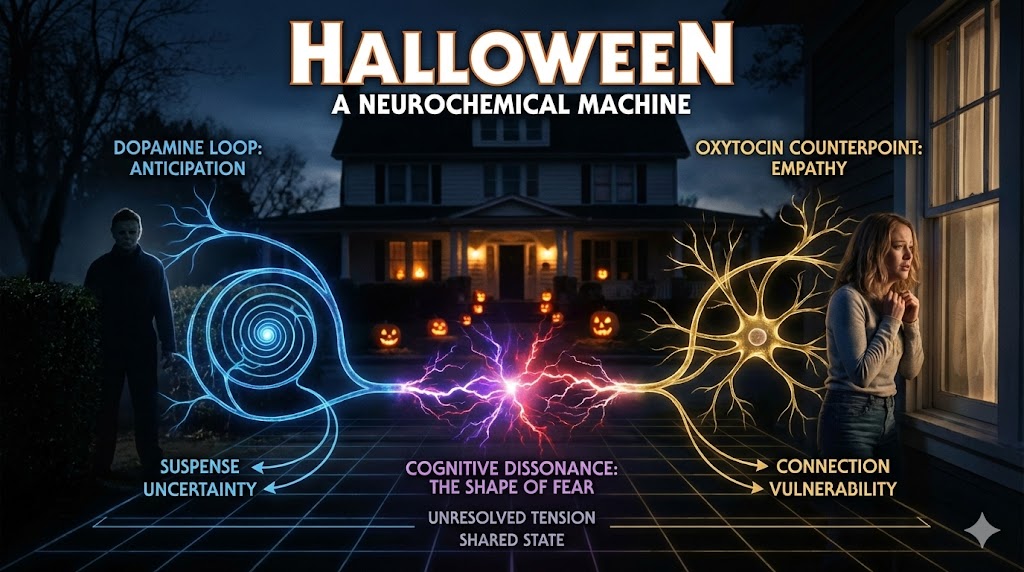

Plain and simple: Empathy.

As discussed in the article “Empathy: Your Story’s Best Friend and Matchmaker for Your Audience,” there are seven universal basic emotions: fear, contempt, disgust, anger, sadness, happiness, and surprise.

Recognizing these emotions isn’t merely enough. We must have a context to give them meaning and furthermore, we need a scale in which to measure their intended effects. That scale, or measuring stick, is relational to the set-up or, as Lisa says, the figurative Why?

In one amateur script, I read not too long ago, the main character’s family is killed within the first three pages. Page four shows the main character gasping, with tears in his eyes and in grief. What followed was more or less melodrama: none of the relationships had been adequately set up to justify our having any feelings of connection to the character. Even on the page, we’re told who these characters are.

Simply put, we didn’t know (or care) about these characters or their relationships with one another to warrant our feeling much of anything for them, let alone understanding what any of it meant.

As readers, we are told how to feel rather than actively shown why, which, in turn, robs us of a sense of self-discovery and makes for a less engaging read.

From the author’s perspective, they were showing and not merely telling (telling as being from a reflective point, looking back where all immediacy is lost.) After all, the family members died a glorious death on the page, and it was shown with visual flair…right? To him, that was the “cause,” and the anguish afterward was the effect. However, that anguish, while meaningful to the character, was meaningless to the reader because ultimately, the emotion – the scene’s power – needed to come from an established relationship between the characters that engaged the audience, who, in turn, invested their emotions in them.

Contrast this with the (albeit lengthy) set-up of a young William Wallace in Braveheart, a small portion shown below.

The story’s crafting, the investment in the characters, and their relationships with one another show where William Wallace’s drive and purpose come from later in the story. This particular scene, showing the burial of Wallace’s family, is also poignant because we had the scene before showing his relationship with his father. One of the movie’s best lines is, “I know you can fight. But it’s our wits that make us men.”

Almost everything we need to know is set up early in the backstory, from the conflict with Longshanks to the love story with Murron and how those two threads tragically intertwine. We’re active participants in the events as they happen so that when Murron suffers her unjust fate, we feel every bit of emotion William does and understand the figurative portion: Why?

The burial of Murron essentially mirrors that of Wallace’s father, both wordless, each family suffering the loss of a loved one. Although the clip here cuts short Murron’s father’s act of forgiveness, in each case, the emotions the audience feels are clearly conveyed not only through the characters and their reactions – but also as a result of witnessing the immediacy of the setups (cause) and payoffs (effect). This “backstory,” had it been delved out in the main narrative, would never have worked – but it does as is because it gives everything else that happens context.

While this may work well for a post-analysis of the film or story, there is still merit in re-examining what Cron refers to as the “myth” for storytelling – how it’s all conveyed on the page. It’s essential to show the effects of sadness (e.g., “crying”), where many writers struggle to write in a way that dramatically conveys a character’s emotions with clarity. Instead, they’ll often resort to a line such as “George wipes his face, dismayed.”

The word “dismayed” ends up being our cheat sheet to the reader regarding how the character feels internally. Still, it should be self-explanatory via the action taken (George wipes his face), depending on the context (setup).

Make no mistake: The level of clarity the reader obtains from a character’s emotion is determined by the quality of the action written on the page.

By explaining “what” the feeling is, we inadvertently take the reader out of the story – robbing them of experiencing it, which, in turn, allows them to be an active participant as they continually ask themselves, “What does this mean?” rather than having it told to them. This is why experiencing the story through its characters and their emotions makes for a more engaging read – and when done correctly, as we’re about to see, a level of clarity and empathy can be obtained within the reader.

With seven universal emotions, many of them used repeatedly throughout a screenplay, the challenge becomes how can they be conveyed without saying the same thing over and over? The short answer is twofold:

1) don’t write the emotion, and

2) it depends on your character.

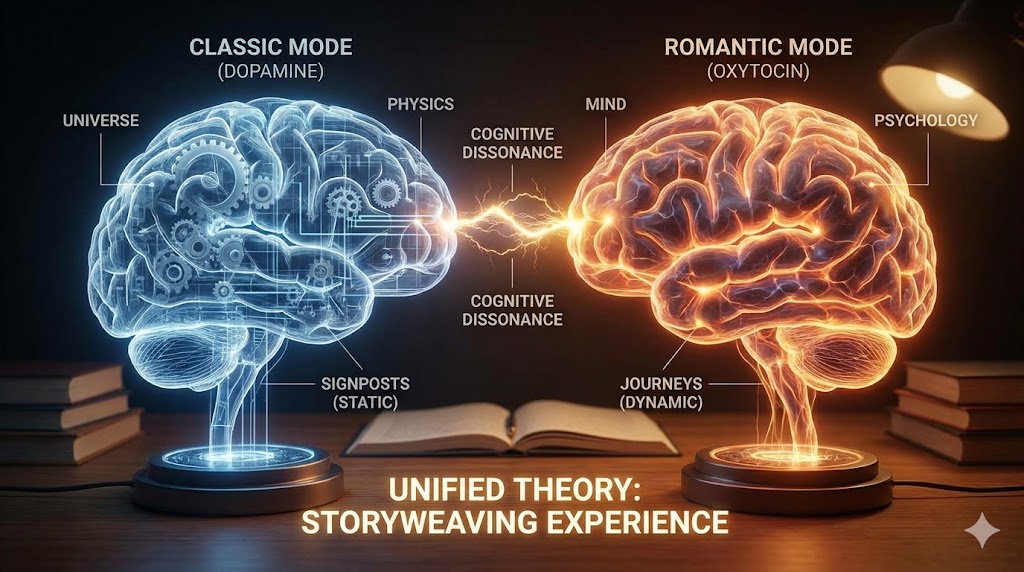

Emotions, while universal, stem from the inside. They’re internal, and it’s not “visual” to state the emotion itself. In doing so, we’re not defining the meaning of the emotion to what degree. What defines characters is their actions. In turn, these actions – and how they’re written – cue the reader into the character’s mindset.

How often have you read something like “Mike enters the room” or “Mike walks into the room”? That’s not only telling; it’s shortchanging your character an opportunity to define yourself.

Does the context (what the scene is about/the cause) make Mike stumble into the room? Could he bolt? Dance? Creep? Sneak? All of these can be useful in giving the scene more context, or we could give the reader a visually negative impression of Mike himself by layering the action with Anthropomorphism by saying, “He slithers into the room.”

Likewise, a woman waiting for her doctor’s test results isn’t going to just “sit in the doctor’s office a nervous wreck.” A nervous wreck is how she feels inside, so the question is, how do you, as a writer, convey that emotion outwardly?

Again, it depends on the character.

She could sit slumped, arm pinned to her chest, oblivious to a child smiling at her. She could be in total denial and carry on like she’s at the hairdresser instead. Or she could repeatedly unlock and lock the clasp on her purse.

Anger is a prevalent emotion in screenplays, but it can be conveyed in several outward expressions/actions depending on the character. Sarcasm and passive-aggressiveness are two ways anger manifests itself in dialogue, but some characters may very well do nothing but smile while others repeatedly cut people off while talking.

In A Few Good Men, we get a taste of a number of actions fueled by Col. Nathan R. Jessep’s anger, contempt, confidence, disgust, disbelief, frustration, rage, pride, among many other emotions that play out like a sliding scale until we get an explosion:

They key here is to identify the prevailing emotion(s) in a scene and find ways to dramatize their outward manifestation.

In A Few Good Men, those emotions come rapid-fire because they’re volleyed back and forth as a result of Lieutenant J.G. Daniel Kaffe’s questioning. Each character spurns a new emotional beat in the conversation, which becomes a game of hot potato, with one character upping the other in intensity. But it’s those beats that ultimately provide us with that measuring stick, from contempt to the explosive admission, giving the scene its power (and meaning).

Understanding these two virtues of “Show, don’t tell” will go a long way to ensuring your audience develops empathy and understands why your characters are the way they are, act the way they do, say the things they say, etc.

Knowing this, an excellent challenge to partake in rewriting is to go through a script and identify scenes that are emotionally charged, looking for words that tell the reader what’s going on and replacing them with specific actions that help define your character. Do this, and your readers will become more engaged, putting the pieces together like we do in real life via non-verbal communication.

If you find yourself getting stuck – keep in mind that you write the reaction to the emotion, showing its manifestation externally, not the emotion itself.

A good resource for any writer is Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi’s The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression. This invaluable tool takes those seven universal emotions and breaks them down into many commonly used terms associated with each, providing examples of mental responses, internal sensations, and physical signals.

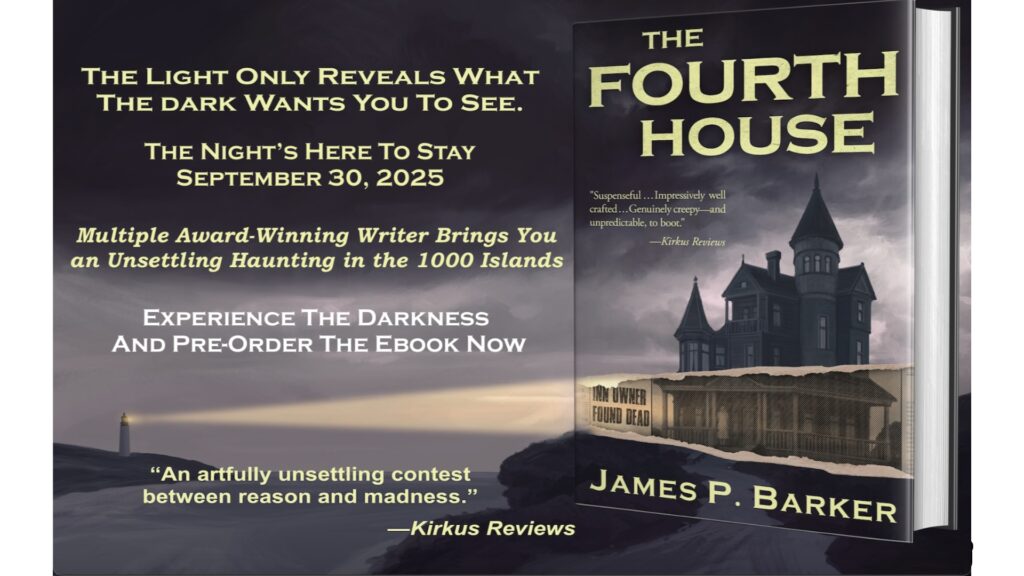

Written By: James P. Barker

3 Responses

You write with such clarity of thought and articulation. Its always a pleasure to read what you write and always a tremendous surprise that in the end I could actually understand what I read.

Most current writing on “Story” is essentially, just a mangled take on Aristotle or so analytically overbearing as to be meaningless.

Write a book man. I’ll buy an autographed copy.

Thank you for the kind words! Who knows…if I write enough articles, a “chapter” at a time, I might just have one ready! It certainly is helping me to organize my own thoughts (and prompting me to go back at my own scripts and practice what I preach.)

I thoroughly disdain “show don’t tell”, and avoid rigorously all works of literature following that injurious commandment and requiring empathy to be read. Therefore, I cannot be persuaded into abandoning my deliberately and shamelessly tell-heavy style.