“For there is nothing heavier than compassion. Not even one’s own pain weighs so heavy as the pain one feels with someone, for someone, a pain intensified by the imagination and prolonged by a hundred echoes.”

–Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

The Woodsman Showcases and Unconventional Use of Empathy

The Woodsman is not an easy movie to watch. Its main character, Walter, played by Kevin Bacon, tries to adjust and assimilate back into society after twelve years in prison. That Walter has a dark secret – he’s a child molester – along with urges he continually fights to control, make him a rather unsympathetic character as his inner turmoil often results in a curt and abrasive outward persona towards others. Yet, in the midst of all, we can’t help but let the film’s dramatic question, whether Walter will succumb to his desires again, draw us in despite a host of his undesirable traits causing discomfort with the viewer.

In a previous article, Empathy: your story’s best friend and matchmaker for your audience.Empathy: Your Story’s Best Friend and Matchmaker for Your Audience, I noted some of how to build empathy for a character that may otherwise seem unrelatable—some of which are present in The Woodsman to understand what Walter is up against in his quest for redemption:

Vulnerability

Having just been released from prison, Walter finds himself in a job with a thankless boss. The only reason why Walter got the job is because of the excellent work he did for his boss’s father. Nobody else knows Walter’s secret, but plenty of prying eyes are scoping out the new guy who prefers to be left alone.

It isn’t long before he’s painted as “damaged goods.”

Unjust Treatment

This may depend on the individual viewer and their perceptions of justice.

Despite the anger Walter harbors within, we get a sense of where some of it comes from. Once the cat is out of the bag, certain people – even the Sergeant assigned to check in on him – seem intent on watching Walter fail.

These people may seem to have questionable morals and perhaps more negative traits than Walter himself. Their actions are immediate, so we have an opportunity to witness and feel them, whereas Walter’s actions happened years ago. The audience is never privy to them, and their impact is diminished somewhat despite their effect.

What makes this tilt empathy slightly to Walter is–

Change

The fact is Walter is making an effort to change. He has uncomfortable exchanges with a workplace fling in Vicki (played by real-life wife Kyra Sedgwick), the Sgt. assigned to look over him, co-workers, a brother-in-law, and a therapist. Most of the conflict results from Walter’s own demons, but he never chooses to succumb to them altogether – giving us some hope he’ll find redemption.

Suffering

There’s no doubt that Walter is suffering from his past exploits and current state of affairs via the motif of the recurring bouncing red ball. While, as viewers, we might distance ourselves from what Walter has done, we still connect on some level to fighting inner compulsions and urges.

There’s also a sense that Walter is willing to suffer in silence rather than negatively impact another person’s life. With Vicki, Walter attempts to push her away, citing her low self-worth.

As we’ll see at the climax, Walter flat-out hates himself.

Authenticity

Despite his secret, Walter acts authentic and refuses to put on a false front.

Even when talking to an eleven-year-old girl, he’s incredibly straightforward and honest in answering her questions. In short, Walter knows his shortcomings and understands why people won’t accept him. This level of self-awareness ultimately drives his fearful behavior: push them away and keep your distance before they can do so first . . . because they’ll never understand him in return.

None of these make Walter “likable” the least, but they provide us with the context to understand him. When we learn Walter’s living across the street from a grade school early on, it doesn’t strike us because we don’t know his secret. However, when we find out, we’re left to wonder . . . when will Walter’s demons get the best of him?

Just halfway into the movie, Walter follows a young girl into a park. He briefly discusses with her, but she quickly becomes uneasy when he declares himself “a people watcher” rather than a bird watcher. She excuses herself, noting her father likes her home before dark.

This, of course, is merely set up. The girl will find Walter sitting alone in the park later in the film’s emotional wallop of a pivotal scene, fraught with subtext, unexpected twists, and, above all else, empathy.

Please be forewarned – this is not an easy scene to watch due to the subject matter, but it’s perhaps the mirroring of damaged souls which makes it so powerful and worth analyzing.

Empathy, as noted by Hodges & Klein in Regulating the costs of empathy: the price of being human. Journal of Socio-Economics:

“has many different definitions that encompass a broad range of emotional states, including caring for other people and having a desire to help them; experiencing emotions that match another person’s emotions; discerning what another person is thinking or feeling; and making less distinct the differences between the self and the other.”

In this pivotal scene from The Woodsman, it’s important to note that an audience’s empathy for a character can be influenced by their relationship with others. We see much of what others think of Walter, with many making little attempt to understand him or give him a chance to redeem himself. The cards are stacked against him, much like the setting and events that define Red’s perspective in The Shawshank Redemption.

What gives this scene its power and makes it resonate is that Robin isn’t about to become a victim – instead, she is a victim, and to make matters worse, it wasn’t by some stranger in a park.

Before this, Walter confessed to Vicki with a disclaimer: “It’s not what you think. I never hurt them.” This is easy to say for the perpetrator whose life continues far removed from the crimes they’ve committed against others. They never have to see the everlasting effects manifest upon their victims. Naturally, this is Walter’s perspective – one that’s challenged when confronted with a victim and witnesses first-hand the pain someone else has caused from the same behaviors.

When Robin says she doesn’t like it when her father asks her to sit on his lap, Walter has absolutely no understanding as to why she wouldn’t because he’s only seen the act from his perspective.

You can see it in Walter’s face as he holds her hurtful gaze. His smile withers as he tries to comprehend, ultimately asking confusedly, “Why not?”

Robin, in turn, goes into avoidance and withdraws, prompting Walter to ask a bevy of questions based on his personal experience. This is Walter’s attempt to make a connection. To understand. To empathize.

Robin, however, battles her own inner feelings and clams up. She gazes through her binoculars as a means of escaping from the moment, but it works for only so long until she breaks down in tears.

At this moment, Walter begins to understand a victim’s emotional pain. His head shakes as he reaches a level of self-awareness that begins to shift his perspective—but then the unthinkable happens.

While Walter looks away in shame, Robin stares at him with her own level of empathy. Despite the pain it’s caused her, she becomes selfless and offers herself up to him. Walter declines, unable to indulge his demons any longer after seeing the pain of another.

But the scene doesn’t end here.

An eleven-year-old child whose innocence we can only guess has been lost at this point still manages to do something very innocent: she shows compassion and hugs Walter. By no coincidence, Robin—as she notes, “Named after the bird”—symbolizes growth, renewal, and the wisdom of change, which her character influences upon Walter.

At the climax of the film, shortly afterward, Walter finds a level of redemption by attacking what turns out to be a pedophile stalking children right outside his window. Having noticed the man earlier, the viewer, at this point, is unaware of the man’s culpability – even so after the fact – until the Sergeant appears knocking at Walter’s door, his demeanor changed toward him as he recounts the attack on the known pedophile with an understanding of who did it.

Empathy in The Woodsman is essential to the story’s structure and overall message. It has a clear purpose in telling the story of change for Walter. It is used effectively to drive that change – perhaps less significant for the audience in its relationship to him than the other characters, particularly Robin. However, her act, in return, and her empathy as a victim help transform Walter and give the story depth and meaning.

In the following article, I’ll explore a much-loved blockbuster Pixar film that surprisingly does the complete opposite and uses empathy all wrong. Until then, here’s the trailer for The Woodsman.

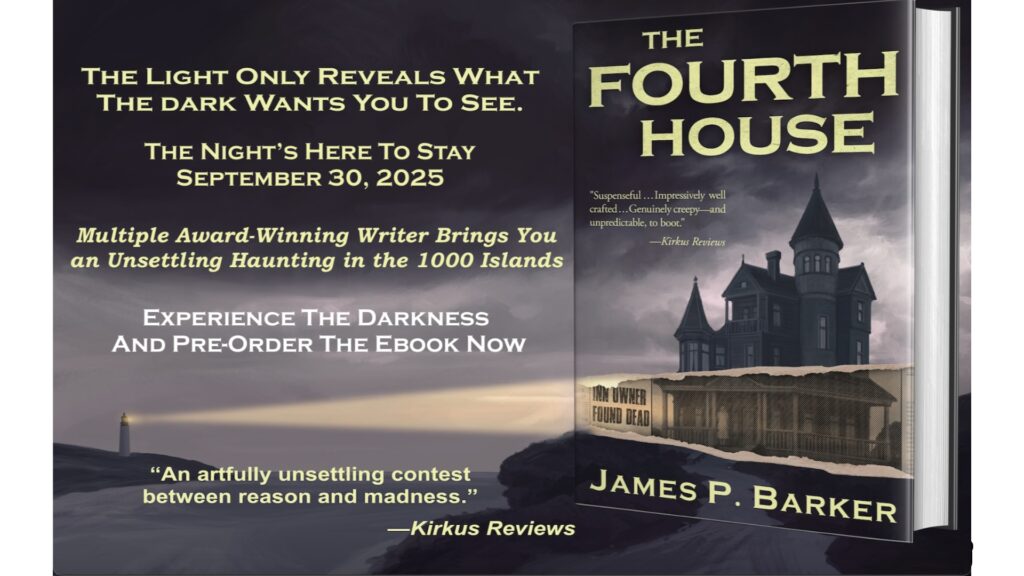

Written By: James P. Barker

6 Responses

My favorite article so far. Forgot all about this movie, but never again; it’s too good to let it slip through the cracks. HBO’s “Oz” might be another great source of unlikable but interesting characters to study. I wish writers would think of humanizing their villains more often instead of making them so ludicrously easy to hate (Joffrey from GOT comes to mind). Obviously Walter is not the villain, but his traits are similar to one, and the writer (and Bacon, of course) turned him into a human being, not a cartoon.

All in empathy like you say. I’d be interested in doing a scene-by-scene analysis of the movie one day, because it’s not easy what they pulled off here.

This will be a wild contrast to the article I plan on doing next. Here we have a movie about a child molester that uses empathy to its utmost power to embody forgiveness and redemption – something that, of all things, goes wrong in one of Pixar’s most loved films. It’ll be interesting to see the response to that article because I think the way the story unfortunately plays out reflects certain attitudes and beliefs in modern society. Absolutely amazing the differences in approach with a movie aimed at KIDS desensitizing them to positive reinforcement to a degree vs. a movie about KIDS being victims yet empowering them.

Can’t wait to read it!

Wow, terrific article, moving scene, took me to tears. :-/ sad sad subject matter.