Part 1: The Philosophical Foundation — Pirsig’s Quality and the Dual Modes of Perception

“The place to improve the world is first in one’s own heart and head and hands, and then work outward from there.”— Robert M. Pirsig

The beginning was not a theory on immersive storytelling.

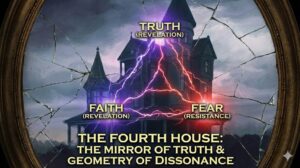

It was a feeling — a pulse of recognition that something in my novel, The Fourth House, carried more than story, more than plot or structure. It resonated with my editors, one of whom said they didn’t see the ending coming, and, upon finishing their edits, went back and re-read it to see if they had missed anything. They did not, stating I had walked that line without a hitch. I initially attributed that to cognitive dissonance, but there was more to it than that.

There was balance and dissonance in equal measure, like two notes vibrating against each other until a third, truer tone emerged. That tone was what Robert Pirsig once called Quality — the leading edge of reality — in his philosophical inquiry work, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

When the manuscript was finished, the question came: how to explain it? What was this thing that seemed both classic and romantic, both precise and ineffable? A query letter demanded category, but the work itself refused to be caged. Somewhere between intuition and intellect, the answer began to shimmer on the horizon as I began analyzing the story through Pirsig’s Metaphysics of Quality.

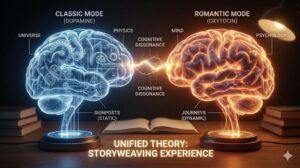

Reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance again was like finding an old map with a new compass. Pirsig’s division of the world into classicism and romanticism mirrored the very architecture of The Fourth House: analysis and emotion, design and experience, mind and heart. The novel, adapted from a screenplay I had penned years earlier, it seemed, had been built upon those twin foundations all along, only unconsciously so. Even the words after the dedication and before the story began echoed straight from Pirsig’s book without my realizing it. “The more you look, the more you see.” How appropriate.

It was Pirsig, too, who articulated the difference between observation and true immersion long before I sought to apply it to story:

“You see things vacationing on a motorcycle in a way that is completely different from any other. In a car you’re always in a compartment, and because you’re used to it you don’t realize that through that car window everything you see is just more TV. You’re a passive observer and it is all moving by you boringly in a frame.

On a cycle the frame is gone. You’re completely in contact with it all. You’re in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming. That concrete whizzing by five inches below your foot is the real thing, the same stuff you walk on, it’s right there, so blurred you can’t focus on it, yet you can put your foot down and touch it anytime, and the whole thing, the whole experience, is never removed from immediate consciousness.” (Pirsig, P. 4)

This is the pulse beneath the Unified Theory. Most storytelling advice teaches us how to build the car—how to construct a safe, comfortable frame through which the audience views the plot. But true immersion kicks away the glass. It seeks that overwhelming sense of presence where the frame disappears and the story becomes part of your own consciousness.

It was here that the next question arose: If the “cycle” is the superior vehicle for experience, what is the engine that drives it?

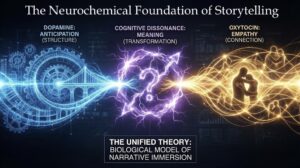

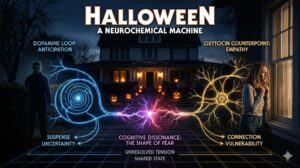

Then came the second recognition — that Pirsig’s metaphysics of Quality might have an analogue in the language of the brain. Dopamine and oxytocin: one driving anticipation, the other connection. Classic and romantic rendered in neurochemical form. The story’s movement between curiosity and empathy suddenly had anatomy.

But something was missing. Between the two stood an unspoken tension — the itch that needed to be scratched. That was Cognitive Dissonance: the mind’s friction when belief and reality diverge, the spark that makes us lean forward, question, and engage. It wasn’t just part of storytelling; it was storytelling. The bridge between the analytic and the emotional, the scientific and the spiritual.

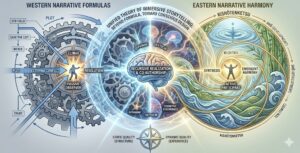

From that moment, the floodgates opened. The frameworks of Pirsig, Dramatica, which I used in rewrites for the screenplay, and neuroscience began to align like gears finding their mesh. Each turned the other, each refined the motion. What emerged was not simply another model of narrative, but a philosophy of participation — a way of understanding story as a living exchange between mind, meaning, and emotion that goes far beyond sensory immersion.

This, then, is the journey of Zen and the Art and Science of Immersive Storytelling: a Unified Theory of Narrative Engagement, from intuition to intellect, from feeling to form, from the solitary writer to the shared consciousness of author and audience.

In short, this project unites philosophy, neuroscience, and narrative structure into a single model that helps explain how stories create immersion, meaning, and emotional engagement.

Below, you’ll find the opening section of the Unified Theory, released in weekly, sequential parts. Each installment builds toward a complete framework for understanding immersive storytelling in both art and science.

“The place to improve the world is first in one’s own heart and head and hands, and then work outward from there.”— Robert M. Pirsig

“A story is an analogy to a single human mind trying to solve a problem.”— Chris Huntley and Melanie Anne Phillips, Dramatica: A New Theory

Note: This is the third part of a series. The prologue can be found here, with the previous chapters at the bottom of the page. The Neuroscience

“Every now and then a man’s mind is stretched by a new idea or sensation, and never shrinks back to its former dimensions.”— Oliver Wendell

“The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”— Marcel Proust Note: This is the fifth part of a series.

“A person isn’t considered insane if there are a number of people who believe the same way. Insanity isn’t supposed to be a communicable disease.

“The more you look, the more you see.” —Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Note: This is the first in many case

“It’s the boogeyman.”— Laurie Strode, Halloween (1978) Note: This is the second in many case studies on the Unified Theory of Narrative Engagement. Earlier essays