“Nothing will make sense to your American ears and you will doubt everything we will do. But in the end, you will understand.” – Benicio Del Toro’s Alejandro in Sicario.

The opening sequence of Denis Villeneuve’s thriller Sicario serves as a precursor of things to come as idealistic, by-the-books FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) finds herself in something entirely different than expected when storming a compound supposedly holding hostages.

After a brief shootout, Kate and her colleague Reggie (Daniel Kaluuya) find bodies – 42 to be exact – hidden inside the complex’s walls. Still, it’s an explosion that claims the lives of fellow agents, which sets her down a path as a volunteer with the peculiar Department of Defense contractor Matt Graver (Josh Brolin) and the even more mysterious former prosecutor from Columbia, Alejandro (Benicio Del Toro), in their quest to “dramatically overreact,” shake the trees and create chaos to get the man at the top.

Little does Kate realize the trip down that particular rabbit hole will be equally unexpected . . . and cost her dearly when the approach ultimately presents the moral dilemma of whether the means justify the end.

One of the things immediately apparent with Sicario is its exemplary structure, where the main character is separated from the typical protagonist function. As discussed in a previous article, the main character is the perspective the audience sees the story through. In contrast, the protagonist drives the plot – a concept many still seem in the dark about. Here, the audience identifies strongly with Kate because we know as much as she does when she does, as the truth is slowly revealed. We are in her shoes and experience the story vicariously through her vantage point as part of the story’s design.

In one scene, when Kate asks Alejandro if there’s anything she should know, she’s told, “You’re asking me how a watch works. For now, just keep an eye on the time.” Kate and, subsequently, the audience are kept in the dark about what’s happening. She finds herself a fish out of water, having been thrust into situations she readily admits she’s ill-prepared for – and a reality that’s exploited, along with her eagerness/willingness to volunteer, to get those responsible for the events in the opening sequence.

This, however, is not how Kate operates; her core values are set up concisely in the opening scenes. Asked what should be said when she’s told the US Attorney wants a statement regarding the raid and horrendous discovery of bodies, Kate replies, “The truth.” In the following scene, she and Reggie sit like a couple of delinquents waiting outside the principal’s office as their boss, Victor Garber (David Jennings), discusses options behind closed doors.

“You did this by the book?” Reggie asks, to which she replies, “Of course.” In assembling a team to go forth, Matt sees Kate as “a (by-the-book) thumper,” but Reggie, with his stellar record and law degree, is a liability when he retorts, “No lawyers on this one.”

This sets up the clashing perspectives as Kate refuses to accept any modus operandi other than standard procedures and protocols, always doing things by the book despite, as her superior gets her to acknowledge, there is little to no evidence of success on the streets as a result of such idealism. “So if your fear is operating outside of the bounds,” Garber tells her, “you’re not. The boundary has been moved.”

Great storytelling finds conflict on multiple levels, never confining it to a simple protagonist vs. antagonist context, and Sicario is no different. In fact, much of the conflict occurs between members attempting to operate together on the same team. Very little of the story deals directly with antagonistic forces (more so the effects), which is appropriate considering that the film plays out as a mystery thriller.

The actual conflict comes from Matt/Alejandro’s perspective that he refuses to accept doing things “within bounds” as the only means of achieving the objective. Matt attempts to get Kate to understand when he says, “You’re giving us the opportunity to shake the tree and create chaos,” noting how things are changing when he adds, “This is the future, Kate!”

As such, the by-the-book approach she evaluates everything against is problematic to what the clandestine operation is really trying to accomplish. Their inability to be open without exposing ulterior motives furthers that conflict and creates doubt – mainly when Matt/Alejandro use understatement as a form of denying her the truth, giving her just enough information that she continues to go along (“We’re going to the El Paso ‘area,'” for example, understating the fact they’re actually going across the border into Juarez.)

The conflict between these two perspectives drives the heart of the narrative. They both seek the same thing but have differing opinions about how to pursue it. Kate’s continual indiscretion is an effect of their relationship, which centers on manipulation. Her involvement is needed because an attached domestic agency (the FBI) gives the CIA legal authority to operate within US borders.

“I told you you’d be useful, too,” Matt says when the cat’s out of the bag. Realizing they’ve been used from the start, Reggie tries to persuade Kate to leave the operation – but Kate opts to stay the course and participate in the planned raid of the tunnels identified as a central point of entry for drug running by the cartel. She’s been used, but now she is driven by the need to know why.

What follows is one of the story’s pivotal sequences: conflict comes to a boil, both physically and emotionally, when Kate separates from her group, goes through tunnels, and sees Alejandro in action. Her response is typical of her nature: she can’t accept what’s happening and wants to arrest him. His response is typical, too: he shoots her. Twice. Shots that knock her down but are ideally aimed at her protective gear and don’t penetrate. Alejandro’s captive, a rogue state police trooper, utters a single word that will lead Kate to the truth: “Medellín?”

Picking herself up, a gasping Kate seeks out Matt and sucker punches him. A short altercation ensues, handily won by Matt as he tries once again to get her to see their approach from a more objective view:

MATT: You went up the wrong tunnel. You saw things you shouldn’t have seen.

KATE: What is Medellín.

MATT: Medellín? “Medellín” refers to a time when one group controlled every aspect of the drug trade, providing a measure of order that we could control. Until somebody finds a way to convince 20% of the population to stop snorting and smoking that shit . . . order is the best we can hope for. What you saw up there was Alejandro working toward returning that order.

KATE: Alejandro works for the fucking Columbian Cartel. (She laughs in disbelief, realizing…). He works for the competition.

MATT: Alejandro works for anyone who will point him toward the people that made him. Not us. Them. Anyone who will turn him loose. So he can get the person who cut off his wife’s head and threw his daughter in a vat of acid. (RE: another look of disbelief from Kate). Yeah. That’s what we’re dealing with.

Despite this and now knowing Alejandro’s family’s fate was sealed because of his actions as a prosecutor – Kate continues to evaluate everything against the rule of law.

KATE: He can’t do this. He can’t. I’m sure as shit not the person you’re going to hide it all behind. I’m going to talk. I’m going to tell everyone what you did.

MATT: That would be a big mistake.

At last, Kate, as well as the audience, fully realizes the level of manipulation that has occurred and why she was “chosen” for the role under the guise of volunteering: she’s a thumper. She goes by the book. And the only way the outcome will be a success is if she ditches her principles and lies about what happened, giving the operation credibility.

Alejandro, meanwhile, as the protagonist, sets off to accomplish the story’s objective while enacting revenge with ancillary support from the team. He is “Sicario,” a hitman made by consequence, and his vengeance is ruthless as he takes out drug lord drug lord Fausto Alarcón – the necessary step toward restoring some semblance of “Medellín.”

As Kate stares from her balcony, puffing away on a cigarette, disillusioned by all that has happened, she is startled by a noise from inside.

ALEJANDRO: I would recommend not standing on balconies for a while, Kate.

Kate hesitantly enters the living room.

ALEJANDRO: You look like a little girl when you’re scared. You remind me of my daughter they took from me. I need you to sign this piece of paper.

He hands it to her, her eyes searching, reading in disbelief.

ALEJANDRO: It basically says, everything we did was done by the book.

KATE (softly): I can’t sign this.

ALEJANDRO: Sign it.

He takes her hand, comforting her as she tears up.

ALEJANDRO: It’s ok. It’s ok.

KATE: I can’t sign this.

Even then, when Alejandro puts the barrel of the gun under her chin, Kate reacts with disbelief as she emits a gasp.

ALEJANDRO: It would be committing suicide, Kate.

And she signs.

ALEJANDRO: You should move to a small town where the rule of law still exists. You will not survive here. You are not a wolf, and this is the land of wolves now.

The pressure is high for Kate to give in, which she does—her signature signals a successful outcome to the story goal. Her change is complete: She finally sees that while she can’t win the argument by signing, she’s reevaluated the events and is letting the Country “win” by regaining some measure of control. There’s one issue left to decide: Has Kate overcome her personal problem?

As Alejandro walks away in the parking lot, Kate grabs her gun and aims it at him from her balcony. Sensing this, Alejandro faces her as if to ask, “Even now, you’re still evaluating what the right thing to do is?” Kate just stands there, full of angst and disillusioned, finally lowering her gun and letting him go. While she’s able to change her nature to fulfill the story’s outcome, she’s unable to quell her personal problem that drives her, evaluating against the rule of law – and it’s a problem that we suspect will continue to haunt her long after the story is over.

In addition to creating conflict on multiple levels, great storytelling can also present an argument and persuade its audience, challenging them to change their own beliefs throughout its unfolding. In Sicario, we’re thrust into Kate’s perspective and are asked to see things as she does – more so because most of us share the same values and beliefs in the rule of law and a just system.

Through her, the author presents their moral argument along with a separate viewpoint that is, more or less, diametrically opposed (a concept previously discussed here). As seen through Kate, the more details come to light, the more we question our beliefs and values.

There comes a point in the story when all the cards are turned over, and we find ourselves questioning whether Kate is right or not. The elements of the backstory are purposefully parsed out until we get the truth—which also provides justification from the opposite perspective—at which point everything comes to an emotional (and physical) boil. Kate wants prosecution, but Alejandro serves as a symbol of that failed ideology, having suffered greatly himself for it.

When Kate doesn’t consider any of this, we not only fear for her safety but also come to detest—if only for a bit—her stubbornness when she says she’s going to rat her team out. As such, the author has dramatically presented their complex moral argument and impacted the viewer’s perspective, challenging it and asking us a simple question every great story does: What would we do if we were in Kate’s position?

Author’s Note: The concepts used in this analysis are based on the Dramatica theory of story without referring to its various components, which would have required going into much greater detail. If you’re interested in a fully comprehensive Dramatica analysis, please check out Jim Hull’s excellent article on Sicario, which humbles any attempt to speak authoritatively on the subject here.

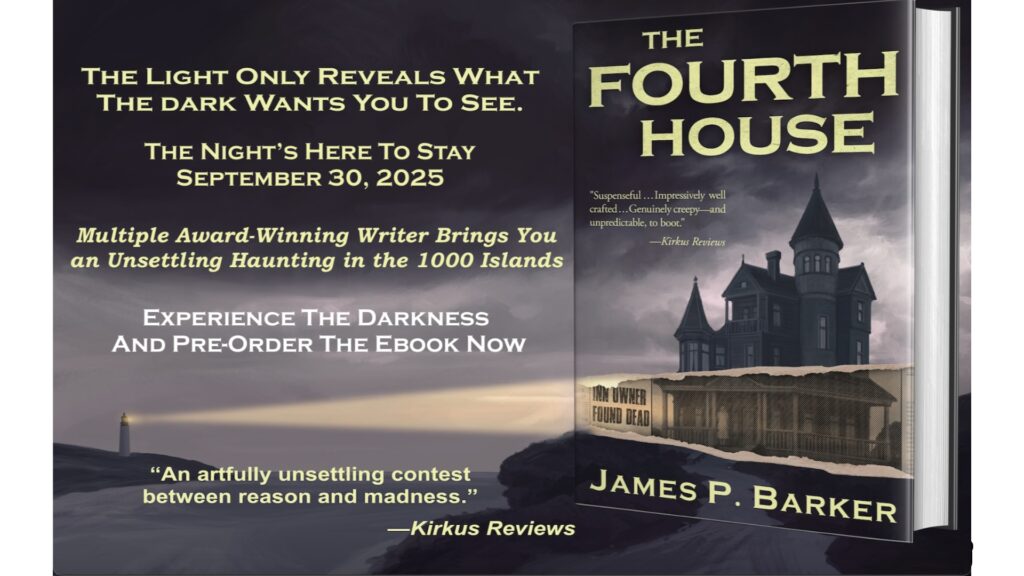

Written By: James P. Barker

One Response

nice post, keep it up