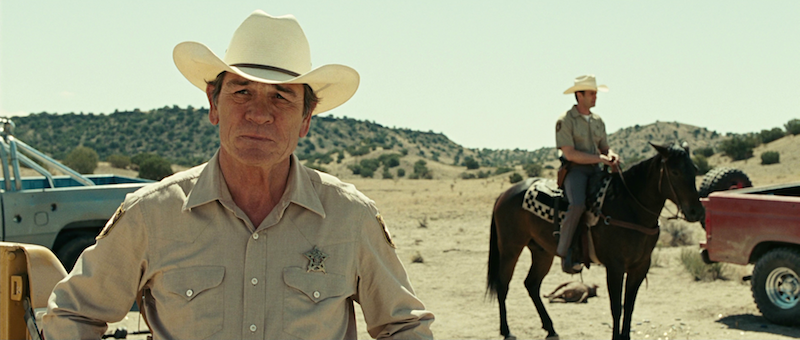

“You can’t help but compare yourself against the old-timers. Can’t help but wonder how they would’ve operated these times.”

-Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, No Country for Old Men, screenplay adapted by Joel & Ethan Coen based on the novel by Cormac McCarthy

No Country For Old Men Left More Than A Few Confused. Don’t Worry. It Was By Design.

Loved the movie. Didn’t get the ending. Why was that?

Many moviegoers shared those words upon viewing Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2007 Academy Award-winning film No Country for Old Men, but perhaps they did not realize that’s exactly how the filmmakers wanted it to be.

To understand this, we must first realize that all good stories—in addition to a compelling plot—have a main character who provides the audience with a number of important functions, perhaps none more so than perspective. Perspective allows us to empathize with characters, giving us the opportunity, safely seated in the audience, to experience the trials and tribulations of someone else while figuratively walking in their shoes.

Emotions, in turn, give meaning to a story – often attached to thematic elements and what “the story is really about” vs. the constructs of a story in terms of events. Without emotions, there’s no meaning; a story without meaning is merely a sequence of events – a plot – that ultimately has nothing to say. Perspective, however, is what allows us to connect to a character, often seeing and feeling their transformation as events unfold, forcing them into a series of decisions and actions that result in either a fundamental change within them or cause a shift in the world, and/or others, around them.

In No Country for Old Men, some audience confusion can be attributed to the fact that the protagonist, Llewelyn Moss, isn’t the main character. What’s the difference, you might ask? A protagonist, by definition, is typically a character who drives the story’s plot and seeks a resolution to its central problem. A main character, a separate story function often paired with the protagonist function in American cinema, provides perspective.

Choosing who the main character is in a story is perhaps one of the most crucial decisions one can make because it’s the character whose eyes the audience will see the story unfold and experience its emotional core and themes. Examples of these functions can be found in The Shawshank Redemption and To Kill a Mockingbird, where Red and Scout, respectively, serve as the main characters through which we experience emotions.

Changing the perspective to another function (character) in the story can significantly change its meaning (simply imagine what kind of story To Kill a Mockingbird would be had it been told through the eyes of Boo Radley.)

In No Country for Old Men, we’re essentially bystanders to the events unfolding as Llewlyn Moss drives the plot. From finding the loot to his fateful decision to bring a shooting victim water hours afterward to his attempts to outrun Anton Chigurh, we’re observers watching him – but never really encapsulating a worldview from him. That function of the story comes from Sheriff Bell, who, just like Red and Scout, provides a voice-over narration, which is our second clue as to whom the story is really about (the first being in the title itself, No Country answering “what?” and for Old Men answering “who?”

Another popular complaint with some audience members that parlayed confusion was having Llewelyn’s death occur offscreen. To them, it felt a bit of a cheat to have so much story and time invested in a protagonist only to have him meet his fate away from the camera – but this, in fact, is central to the story’s thematic structure because we, the audience, learn of his death alongside Sheriff Bell, thus experiencing the confusion and shock just as he did. That the film’s only use of a non-diegetic soundtrack score happens at this precise moment heightens our emotional response, which is seen and felt from Bell’s perspective.

“The crime you see now, it’s hard to even take its measure. It’s not that I’m afraid of it. I always knew you had to be willing to die to even do this job — not to be glorious. But I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand. You can say it’s my job to fight it but I don’t know what it is anymore.“

Sheriff Bell – No Country For Old Men

Thus, Sheriff Bell further laments in the opening voice-over, hinting at the confusion, the theme, and, more importantly, the ending to come, which encapsulates the story’s thematic content.

It’s no coincidence Bell’s newly retired: this world isn’t the same one when he began his job as Sheriff at the age of twenty-five – a time when his father was Sheriff elsewhere, too, a time long gone by when the world made sense. While much could be said about the interpretations of his dreams, the reality is that Bell has retired, not knowing anymore what the “it” he was fighting was – and that scared him because he no longer understood it. Without understanding, meaning crumbles away, leaving only fear, confusion, doubt, and ultimately meaninglessness.

And therein lies the beauty of the ending: we’re confused and still searching for the story’s meaning, thinking perhaps it doesn’t make any sense – yet there we are, right where we were meant to be in Bell’s shoes, feeling the same way he does. All we need to do is see it from his perspective as an old man who longs for simpler times when things make sense. As an old man who finds more comfort and logic in his dreams than in the violent world, he’s withdrawn from while awake – a world that’s ultimately proven to be no country for old men.

Written By: James P. Barker

4 Responses

Hey, mate, fantastic post on the differences between protagonist and main character. I hadn’t thought about it before, but seems you hit the target from a mile away. Good job! FYI, I come from Scriptshadow. Interesting to see what the patrons there are up to. Hope you keep these coming. I certainly enjoyed it–and even better, learned from it.

Thanks for the compliment – I was a bit hesitant to read when I saw it was from “thepissedoffpundit”, lol. I’ll do more in the future, using The Shawshank Redemption and To Kill a Mockingbird, but it’s a concept that’s foreign to a lot of people because most American cinema bundles the two functions together. Separating them can cause a lot of people confusion when trying to provide analysis if they’re not receptive to the notion they don’t have to be the same (e.g. Red vs. Andy, Red being the main character who we feel the story through while Andy drives it, but remains somewhat distant.)

Good writing’s designed to make you feel what the main character does, putting you in their shoes so you learn and feel what they do when they do (we learn of Andy’s escape when Red does).

More importantly, Red carries that transformative message of hope for the audience because most people in this world are cynical; very few of us walk around like Andy!

Anyway, I’m rambling – save it for a later post! Next one up, hopefully tomorrow, will be on A Beautiful Mind’s much misdiagnosed Inciting Incident.