“The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he did not exist.”

-Roger “Verbal” Kint, The Usual Suspects, Screenplay by Christopher McQuarrie.

The Usual Suspects displays some Puppet Master-Level Machiavellianism by its Writer

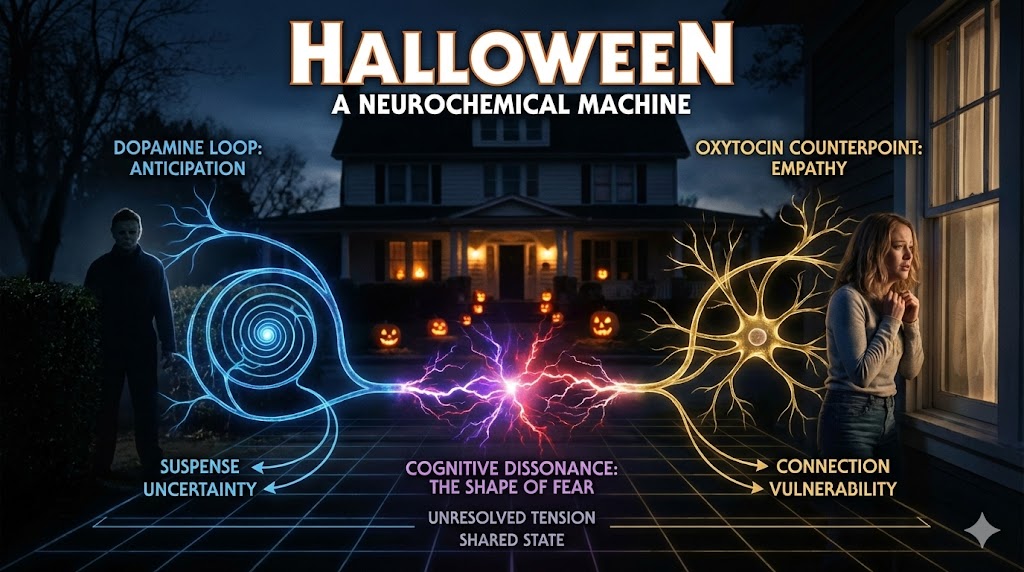

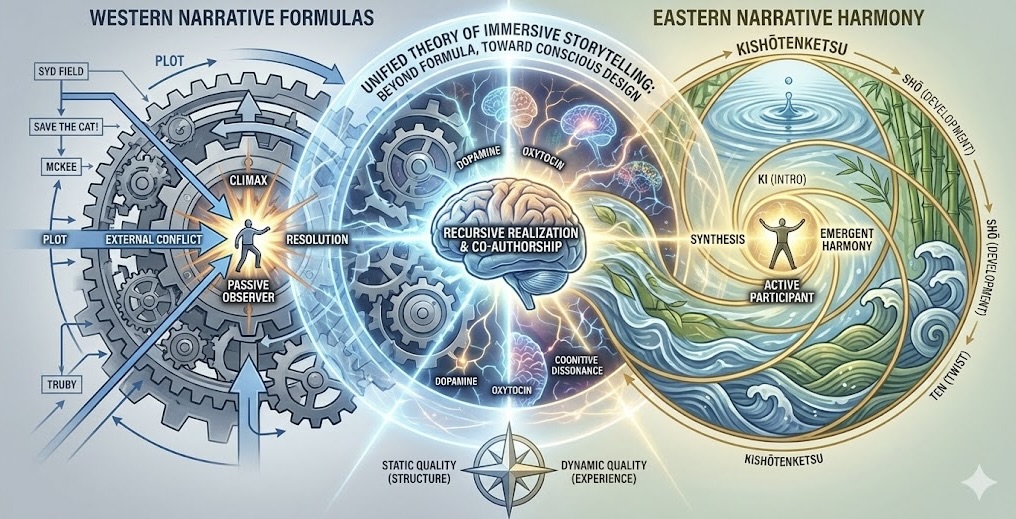

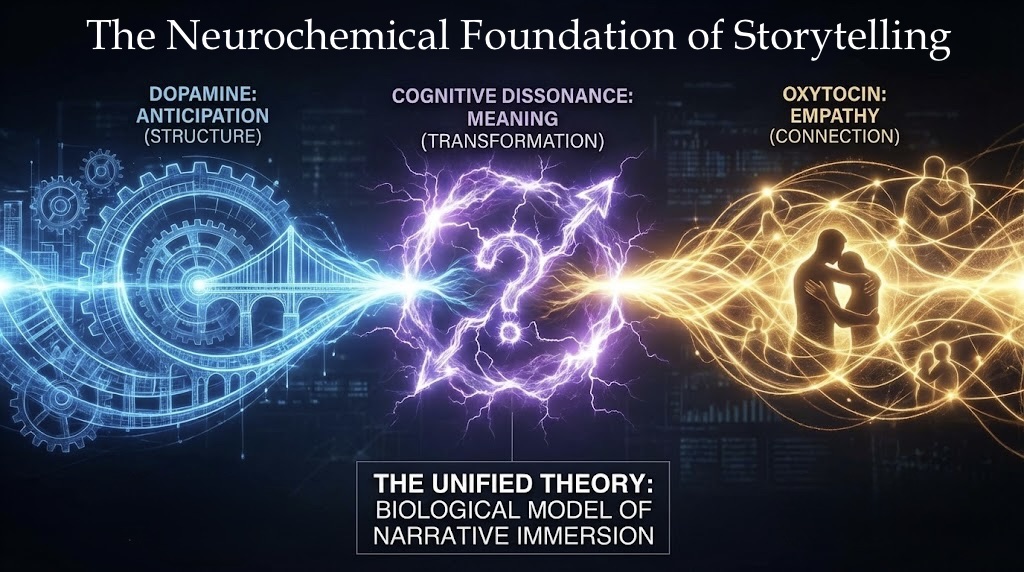

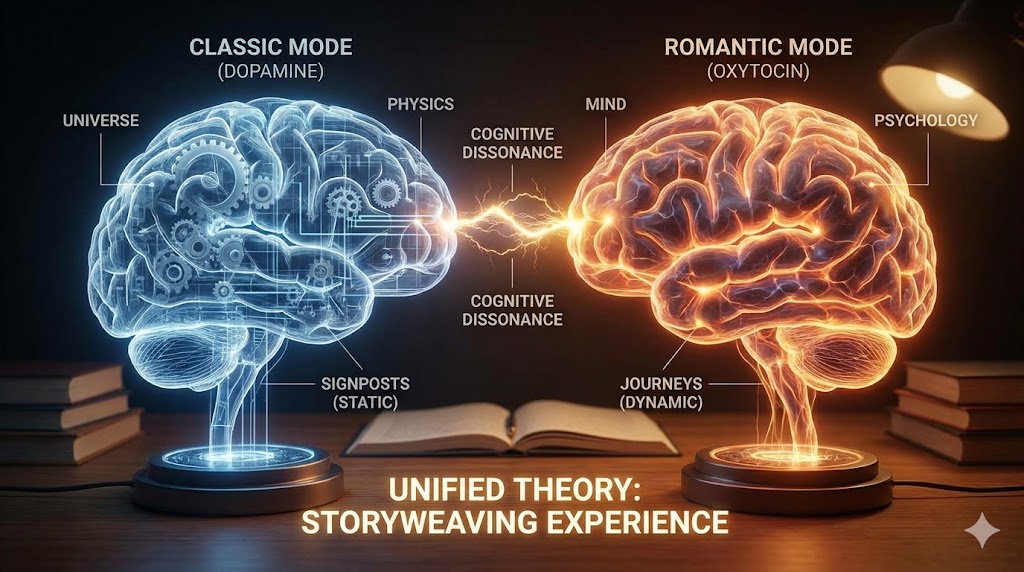

Much effort has been made to define empathy and how it is the ability to emotionally connect characters to one another and subsequently draw an audience deeper into a story, as well as its ability to cause both cognitive dissonance with a main character’s obsessive drive as with Scottie in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, where the audience’s empathy suddenly shifts to the murderer’s accomplice. While most of the discussion so far has been focused on the positive attributes as they pertain to story structure based on audience perspective, there are, as we’re about to see, negative attributes that can be just as powerful in telling a compelling story, creating multi-dimensional characters full of surprises.

Empathy is one of the cornerstones of something larger called Emotional Intelligence (EQ). Not long ago, psychologists began to understand what we know as IQ isn’t necessarily the most significant indicator of success and that there’s a social factor involved – one needs to look no further than perhaps John Nash in A Beautiful Mind for an exemplary motion picture – and that the ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different feelings and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior has a significant bearing on one’s success as well.

In her recent Psychology Today article, The Dark Side of Emotional Intelligence, Denise Cummins, Ph.D., notes

The problem is that EQ is “morally neutral.” It can be used to help, protect, and promote oneself and others, or it can be used to promote oneself at the cost of others. In its extreme form, EQ is sheer Machiavellianism–the art of socially manipulating others in order to achieve one’s own selfish ends. When used in this way, other people become social tools to push themselves forward even at considerable expense to them.

The problem is that EQ is “morally neutral.” It can be used to help, protect, and promote oneself and others, or it can be used to promote oneself at the cost of others. In its extreme form, EQ is sheer Machiavellianism–the art of socially manipulating others in order to achieve one’s own selfish ends. When used in this way, other people become social tools to push themselves forward even at considerable expense to them.

One way to think of Machiavellianism is via the term “puppet master.” They’re behind the scenes pulling the strings and controlling perceptions of others, manipulating them to determine a specific outcome.

As notable documentary filmmaker Ken Burns has said, “All story is manipulation.” However, within the constructs of the story and its telling, we need to have means to manipulate and create deception. If you’ve been reading the other postings on this blog, you can probably see where this is going: deception is based on perception, which, in turn, is rooted in perspective. The main character who wraps this all together in The Usual Suspects is Roger “Verbal” Kint.

What makes Verbal Kint a compelling character is the way McQuarrie has him seemingly manipulated by others throughout the story—and how, in turn, this manipulates us, the viewer—only to have the curtain pulled back to reveal he was the mastermind all along, controlling every thought and move throughout the story.

Much of what the audience thinks, feels, and believes is a direct result of the relationships between characters on the screen and how they react to one another, particularly regarding the main character. Those relationships, in turn, exist to construct the deceit. To McQuarrie’s credit, Verbal Kint is ultimately a villain but comes across as a small-time crook. We sympathize with them for most of the story but marvel at once the final card is revealed.

When looking back at the film and analyzing its structure, we can see how these elements came together and set the deception in motion from the very opening scene from the filmmaker’s perspective:

1) “The Walk” – the gunman quickly walks down the stairs like an average person. When we’re introduced to Verbal later, we’ll discover he has cerebral palsy, which inhibits his ability to walk normally. While it serves as a function for deception, the disability casts Verbal as “meek” and a character we might sympathize with.

2) “The lighter” – the gunman flicks the lighter as he lights a cigarette. As we’ll find out later, Verbal’s condition has left him (seemingly) unable to flick-a-bic, so to speak.

3) “The gun” – The gunman pulls a gun, switches hands, and aims at Dean Keaton. The narrative later notes Verbal’s inability to shoot a gun, much less hold one steady . . . or so we’re led to believe.

4) “Keyser“ – Keaton mocks the gunman, calling him “Keyser” in a tone that suggests he’s not who he says he is (in this case, Keaton knows it’s Verbal in having seen his face and is smart enough to connect all the dots realize who’s really been pulling the strings.

5) “The unreliable narrator” – in the present, we see Verbal as the one recounting what happened. Much like Red in The Shawshank Redemption, we’re immediately cued into his perspective of events – and through the course of the telling of the story, we’ll see firsthand why this device is once again paramount to the narrative and thematic elements.

These five points help set up McQuarrie’s Machiavellian tale, but in a story about a cast of criminals who engage in antisocial behavior, the audience still needs a character who can feel the emotions and become active—and unknowing—participants in the deception.

Enter two factors: the mythos of Keyser Söze and Agent Kujan.

By allowing Verbal to “tell” a story within the story, McQuarrie cued in Verbal’s. Therefore, the audience’s fear for Söze via the slaughtering of his own family by creating the mythos. In contrast, the name became synonymous with a spook story criminals told their kids at night. “Rat on your pop, and Keyser Söze will get you.”

While these guys may be a rag-tag bunch of criminals, they pale compared to the exploits of Söze, who seems to have every one of their numbers. These guys are small potato low-lives in comparison, but it’s their sense of inescapable dread that permeates the narrative as told by Verbal, the victimized cripple who didn’t belong amongst them in the first place.

Conversely, Kujan is the hard-boiled Customs Agent with his perspective of the events and a suspect in mind. Determined to get his questions answered, he blatantly manipulates and belittles Verbal to serve his own purpose: to pin the crime on Dean Keaton, a man he’s been after for years.

In one condescending speech, Kujan threatens Verbal with, “Let me get right to the point. I’m smarter than you. And I’m going to find out what I want to know and I’m going to get it from you whether you like it or not.”

Later he relishes the opportunity to rub Verbal’s apparent exploitation in when “breaking” him to confess Keaton was behind everything, “Because you’re a cripple, Verbal. Because you’re stupid. Because you’re weaker than them.” As we eventually find out, nothing could be further from the truth.

Just like Sam Loomis’s badgering of Norman Bates in Psycho or Scottie’s obsessive drive toward making Judy over in Vertigo, the adverse treatment of one character towards another can cause cognitive dissonance in the audience. Cops are supposed to be good guys after all, but Kujan’s acting like the bad guy here – thus allowing the audience to sympathize with the character on the receiving end.

Whereas Verbal is colored with sympathetic traits – soft voice, crippling condition, sense of humor, easily victimized – Kujan is brash, arrogant, and single-minded, attributes that make him less agreeable to audiences despite the fact he’s supposed to be the good guy/law-enforcer.

Structurally, Kujan’s perspective that Keaton was behind the boat massacre mirrors Verbal’s telling of Keyser Söze’s backstory, providing a counter-argument and planting the seeds for whom the audience will be misled to believe the mastermind was.

Let me tell you something. I know Dean Keaton. I’ve been investigating him for the past three years. The guy I know is a cold-blooded bastard. IED indicted him on three counts of murder before he was kicked off the force…Dean Keaton was under indictment a total of seven times while he was on the force. In every case, witnesses either reversed their testimony to the grand jury, or died before they could testify. When they finally did nail him for fraud, he spent five years in Sing Sing. He killed three prisoners inside.

Of course, I can’t prove this – but I can’t prove the best part, either: Dean Keaton was dead. Did you know that? He died in a fire two years ago during the investigation into the murder of a witness who was going to testify against him. Two people saw Dean Keaton walk into a warehouse just before it blew up. They said he went in to check a leaking gas main. It blew up and took all of Dean Keaton with it. Within three months of the explosion, the two witnesses were dead. One killed himself in his car, the other fell down an open elevator shaft. – AGENT KUJAN

Let me tell you something. I know Dean Keaton. I’ve been investigating him for the past three years. The guy I know is a cold-blooded bastard. IED indicted him on three counts of murder before he was kicked off the force…Dean Keaton was under indictment a total of seven times while he was on the force. In every case, witnesses either reversed their testimony to the grand jury, or died before they could testify. When they finally did nail him for fraud, he spent five years in Sing Sing. He killed three prisoners inside.

Of course, I can’t prove this – but I can’t prove the best part, either: Dean Keaton was dead. Did you know that? He died in a fire two years ago during the investigation into the murder of a witness who was going to testify against him. Two people saw Dean Keaton walk into a warehouse just before it blew up. They said he went in to check a leaking gas main. It blew up and took all of Dean Keaton with it. Within three months of the explosion, the two witnesses were dead. One killed himself in his car, the other fell down an open elevator shaft. – AGENT KUJAN

On first viewing, I don’t think anyone would have guessed the actual plot would have been exposed so openly – yet there it is, hidden amongst dialogue, Kujan himself a bit of an unreliable narrator since he readily admits he can’t prove his story making it a myth in its own right. But somewhere in the middle of these two perspectives, we have a bit of objective truth: the other survivor in the hospital knows the identity of Keyser Söze, and the mere mentioning of his name, referring to him as “the devil,” causes both a visceral (high blood pressure) and emotional (fear) reaction.

Dr. Martin Kildare, Chair of Organizational Behavior at University College London, noted that emotionally intelligent people

intentionally shape their emotions to fabricate favorable impressions of themselves…The strategic disguise of one’s own emotions and the manipulation of others’ emotions for strategic ends are behaviors evident not only on Shakespeare’s stage but also in the offices and corridors where power and influence are traded.

intentionally shape their emotions to fabricate favorable impressions of themselves…The strategic disguise of one’s own emotions and the manipulation of others’ emotions for strategic ends are behaviors evident not only on Shakespeare’s stage but also in the offices and corridors where power and influence are traded.

Kujan and Verbal work this to both ends.

Kujan’s anger and self-righteousness are often masked by a fabricated “good cop” to manipulate Verbal into telling his story, which he then attempts to manipulate to fit his agenda with Keaton. The problem is that Kujan is nowhere near as adept at masking his intentions as Verbal, who goes so far as to play the victim and the fool in an attempt to play off Kujan’s superiority complex and ultimately get the best of him.

While Verbal is ultimately portrayed as having a high IQ in pulling off his deception, the character’s – and film’s – success is partly due to EQ and his ability to discern emotions in others, which opens the door to manipulation.

In other words, IQ may be what enabled him to put the plan together, but EQ allowed him to carry it out. This, in turn, enabled the filmmakers – the real puppet masters – to create a compelling, complex, and memorable character more intellectually engaging than the typical one-note villain who relies on brute force, able to pull strings and control/manipulate those around him – including the audience.

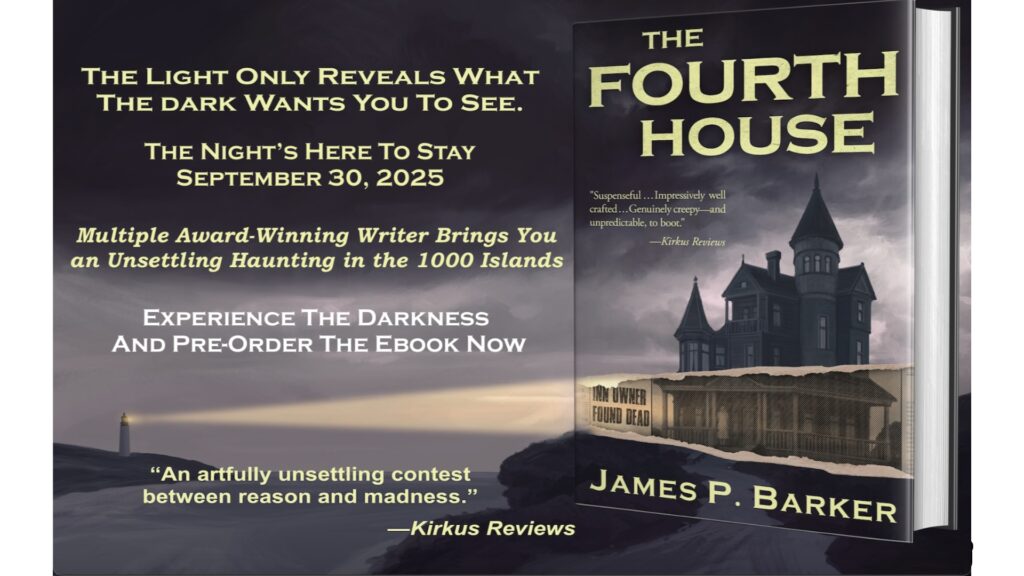

Written By: James P. Barker

5 Responses

Was considering showing this to my friend, a cinema arts major. You just convinced me. Can’t beat the well-constructed plot of this beast, it’s uncanny.

I was surprised reading Roger Ebert’s review recently – I believe he gave it one and a half stars, but he made the observation that he didn’t care for any of the characters. It’s a tightrope writing movies like this; Martin Scorsese made a career out of exploring deviant personalities and people wondered why he never received an Oscar until recently, but that’s the risk one takes on, I guess, as I’ve often felt myself unable to connect to many of them. The films are great to watch, but I found myself essentially one-and-done with many of his for that reason. With regards to The Usual Suspects, I think, as you mentioned, the repeated viewings it earns comes from its plotting (many of the character, on the other hand, are rather one-note.)

I kind of liken the movie to having the filmmakers with a marionette of Verbal, who in turn controls a marionette of the other characters with one hand and a marionette of the audience in the other – angling their perspective so they can only see what he wants them to see, when he wants them to see it.

And that’s another reason why I want to show it to my friend. I’ve seen it enough times that the memory of my first viewing is a little diluted. I do remember struggling with trying to get a handle on what the story really was about, who was the main character, etc.

Watching it now, I do it to watch Verbal expertly lie through the course of the movie. To see the magician do a long trick, basically. The first time around, though, there’s no awareness on the audience’s part of a trick being played, so finding the spine and purpose of the story is almost impossible.

I have to agree with Ebert to an extent. This movie is more of an intellectual trip than an emotional one, so it’s no surprise we’re not connecting to the characters in the way that we would do in, say, Shawshank.

Exactly – it’s not like we’re rooting for Butch and Sundance as they knock off banks, though they have their own coda in doing so – but all the more reason why Verbal is more sympathetic, otherwise it just wouldn’t have been as big of a surprise.