“Feelings or emotions are the universal language and are to be honored. They are the authentic expression of who you are at your deepest place.” – Judith Wright

WARNING: Storytelling spoilers ahead on Pixar’s Inside Out!

Leave it to the storytelling gurus behind Pixar Animation Studio to develop a relatively simple, high-concept story about a complex subject wrapped in a context that is easily understood and universally appealing to young and old alike. Accomplishing this is no easy feat, but the folks at Pixar know perhaps better than any other studio the power of a thematically rich narrative.

The theme, after all, is often thought of as “the heart” of a story, what it’s really about. The heart, therefore, represents that inner journey. In contrast, the plot (events) are typically external to the character, but Inside Out twists this notion and makes the inner (emotional) journey part of the plot. At the same time, emotions are characters who learn and influence one another, resulting in change that ultimately reveals a universal truth. As Lisa Cron wrote in her book Wired For Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence:

“Since theme is the underlying point the narrative makes about the human experience, it’s also where the universal lies. The universal is a feeling, emotion, or truth that resonates with us all.”

Thematically, Inside Out is a surprisingly close companion piece to last year’s Australian indie horror The Babadook. Both films deal with the destructive forces upon the family stemming from the suppression of negative emotions while also exploring narratives through expressionism. Inside Out begins with a brief prologue, associating us with the various emotions, beginning with Joy, quickly followed by Sadness, which she immediately tries to suppress, later declaring, “I’m not sure what she does.”

While the story that follows is a result of the family’s upheaval from Minnesota to San Francisco, moving is not, in itself, the narrative’s inciting incident as Riley does her best to cope with a myriad of symptoms (stemming from moving) without ever consciously realizing what the problem actually is. Instead, the problem is set up externally when Riley’s mother asks her to put on a happy face for her father’s sake.

Riley makes the decision to oblige, at least on the surface, not wanting to disappoint her family – but sacrificing her authentic “sad” self in the process and suppressing her feelings leads to inner turmoil much in the same way Amelia did in The Babadook (but to much less horrific effect.)

The internal portion of the inciting incident is when Riley cannot sustain her happy face in class, causing the struggle within that results in a “sad” core memory as Sadness taints joyful memories with a sense of melancholy and longing. By this point, the story’s goal has been established to ensure Riley stays happy, which requires the suppression of sadness from the other emotions.

Alas, a struggle ensues over the core memory between Joy and Sadness, both being accidentally sucked out of Headquarters to leave Anger, Fear, and Disgust in charge. At the same time, Joy and Sadness embark on an inner journey of their own in the form of a buddy narrative that’s indicative of the “Two-Handed Approach.”

Outwardly, Anger, Fear, and Disgust display themselves in the forms of resentment, anxiety, and sarcasm – mainly directed toward Riley’s father as she continues to deal with the symptoms of her actual problem. This, in many ways, works as much as an allegory for depression as The Babadook is an allegory for the suppression of grief and how those forces act destructively with the crumbling of each of Riley’s “islands.”

Inside, the journey that represents the heart of the story is only beginning for the mismatched Joy and Sadness, who must find their way back to Headquarters through a maze of memories to prevent the destruction of Riley’s personality as they know it, one ultimately influencing the other to change to resolve the story’s problem . . . but which one?

Conventional thinking would have one believing Joy saves the day, restoring the inequity that sadness has apparently caused – but this is a Pixar film and, looking back at the earlier statement regarding the theme, they’ve had a knack for finding the universal truth we can all relate to which, in real life, often comes at the hand of defeat.

Early in the story, Sadness states that when Joy asks why she’s crying, noting it’s the opposite of what they’re going for, it “lets me slow down and obsess with life’s problems.” For Joy, Sadness is a mystery whose only value is negativity and worsening things. It’s a perspective she holds onto for nearly half the story until Sadness’s purpose is deftly illustrated through Riley’s old imaginary friend, Bing Bong, who’s just lost his rocket to “The Dump” and seemingly inconsolable at the thought of Riley being through with him.

Given what appears to be a mild form of depression that mirrors Riley’s own, Bing Bong is unmoved by Joy’s attempts to stimulate and cheer him up – just as Riley was herself by her father’s attempts. Sadness seizes the moment and does what comes naturally, showing us an outcome/benefit to solving the story’s problem: Empathy.

Sadness listens to Bing Bong and encourages his feelings while Joy decries, “You’re making it worse!” failing to realize, at least initially, that she is actually making it better. When Bing Bong finally says, “I’m ok now” and brushes away his candy tears, a device that foreshadows the story’s “bittersweet” ending, a mesmerized Joy is left asking Sadness how she managed to make him feel better.

Only when Joy experiences sadness at the prospect of being forgotten can she finally understand the emotion’s value. Stuck down in the dump with Bing Bong and all the other fading memories, she comes to a revelation when viewing what was once perceived as a “joyful” memory, only to now get an objective view of it and learn that the joy of having her teammates lift her up was actually born from a sad moment having missed the game-winning goal.

“Mom and Dad . . . the team . . . they came to help because of Sadness.” Indeed, facts and opinions can look similar when colored by our perspective, which Joy had alluded to earlier.

Arriving back at Headquarters to save the day, the other emotions are surprised when Joy defers control to a reluctant Sadness, telling her, “Riley needs you now.” Sadness sparks an idea/revelation for Riley, who, still chasing symptoms rather than the problem, has decided to run away to Minnesota, where all her happy memories are. With newfound insight, she returns home, where she lets her true feelings out.

RILEY: I know you don’t want me to, but I miss home. I miss Minnesota. You need me to be happy, but I want my old friends and my hockey team. I want to go home. Please don’t be mad.

Surprised by Riley’s pain, her parents listen, understand, and empathize, telling her they also miss home. Asking her to put on a happy face caused real inner turmoil, allowing, and perhaps even more importantly, accepting her authentic feelings to resolve the story’s central conflict and growth. As Sadness takes Joy’s hand and presses the button on the control panel, a new core memory forms. Equal parts sadness and joy, it’s a complex emotion that reveals the bittersweet truth central to the story’s theme: life is full of sadness and loss, but it’s just as important to experience and express those emotions as it is joy and happiness; they co-exist, sometimes even in the same moments like memories.

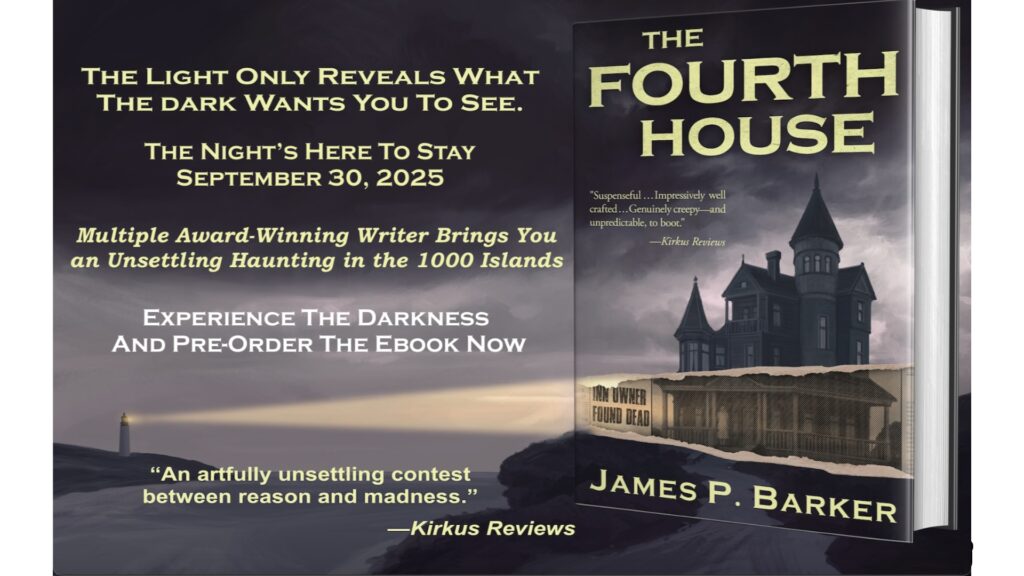

Written By: James P. Barker

7 Responses

Great points! What exactly is the inciting incident in The Babadook?

The Babadook is, much like Star Wars, one of those stories set in motion from the very first frame which is why they’re often overlooked/over analyzed/mistaken. The very opening scene of The Babadook is the death of the husband in the car accident – he’s present for all of maybe two seconds, so if someone blinked they would have missed him. But it’s really what sets the story in motion. The book arriving is just a manifestation of the mother’s inner-struggles and representative of what the story is about (the accident/death being plot related).

Thats exactly what I was thinking too, thanks for the wisdom sir, I really appreciate it. Love your work.